Possessions

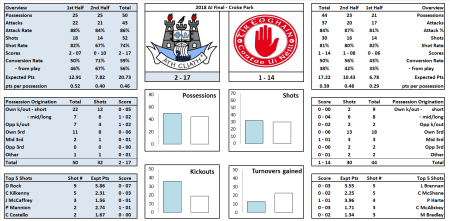

It goes without saying that the first primary objective of any team is to gain control of the ball. In the three most recent meetings between the protagonists (2017 AI semi-final, 2018 league and 2018 Super8) the total possession count is 136–135 in Dublin’s favour. It is somewhat surprising to see things so evenly matched however when we review first halves only Dublin are 69–62 ahead so game state has definitely had an effect on this metric.

Still Tyrone have been better in the last two encounters trailing the possession count at half time 24–23 in the league game and 22–20 in the Super8 contest. The concern here is that both of these contests were held in Omagh with all the built in advantages that entails. It will be imperative for Tyrone that they replicate these Omagh starts in the slightly less friendly environs of Croke Park and, at the very least, get on as much ball as Dublin. And get on it early.

Possession can be garnered in two primary ways. The first is through kickouts and the second is through turnovers (see note1 below). Kickouts are covered in depth below but focussing on turnovers there is definitely a trend favouring Tyrone. They, in their three games against Dublin, lead the turnover count 75 – 64 however that advantage dissipates when it comes to the prime counter attacking turnovers garnered outside your own 45. Both teams have managed to get their hands on 17 turnovers apiece outside the 45 with Dublin producing more (which will become a common theme) scoring 2–04 from these 17 possessions compared to 0–04 for Tyrone (see note2 below).

Tyrone’s turnover advantage is blunted by the fact that they have received the ball more often inside their own 45, giving Dublin time to reset the defence.

Once control of the ball is established the next step is to manufacture a shot. This is the oft referenced transition stage and is generally something that we in the GAA are bad at quantifying. We know, just from visual observation, that Dublin are excellent in this phase but just how good are they? And how do you quantify that?

Using shot totals as one measure Dublin are not that much better. In their three meetings Tyrone, despite having one less possession, actually end up with one more shot than Dublin (80 – 79). That even includes two shots that Dublin got from rebounds (so can’t really be attributed to “transition”). Now there is great disparity game to game (Dublin had six more shots in the 2017 semi-final, Tyrone had eight more in the league game whilst Dublin had just the one more in the Super 8 encounter) but Tyrone have, on the whole, created chances.

As further evidence of Tyrone’s ability to create chances; in their four most recent games (3x Super8 contests and the semi-final v Galway) Dublin progressed 68.9% of their possessions to a shot whilst the opposition combined for 69.3% on this metric. In their last four games, against much the same opposition as Dublin, Tyrone progressed 73.9% of their possessions to a shot. Of late Dublin have not really stopped teams, be it Tyrone or others, from transitioning to a shot.

If there is no discernible quantitative difference between how the teams use the ball then, given that Tyrone have lost the last three encounters by a combined 20 points, there must be quite a large qualitative difference.

When Dublin have the ball

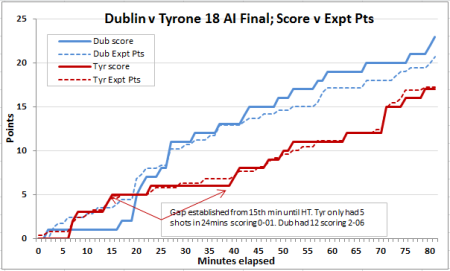

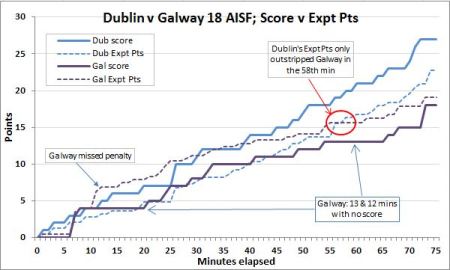

Going into the 2017 final Dublin were recording a quite remarkable Conversion Rate of 61%. That was from five games which included three in the Leinster championship so theoretically that 61% should have been somewhat bloated by facing lesser opposition (that theory was dented when they then went out and hit 68% against Mayo in the final but still …. )

In their last four games, which on paper should have been collectively harder than the 2017 run in, Dublin have returned a quite incredible 64% (see Table1 in the Appendix for detailed player breakdowns). To try and put this into some form of perspective the average Conversion Rate from 2015 to 2017 was 53% whilst everyone else in the 2018 timeframe (Super8s and semi-finals) has hit 55%.

So how are Dublin achieving this?

Frees

Perhaps the most obvious place to start is with their free taking. Dean Rock has been the leading light in terms of accuracy of late. From 2015 to 2017 Dublin converted 82% of their frees (0–93 from 113) with Rock accounting for the vast majority of this; he took 81% of all their frees in this timespan recording a whopping 88% (0–81 from 92) Conversion Rate. Every other free taker was a combined 72% during this period.

Within the four games outlined above Dublin have converted 82% (0-18 from 22) of their shots from frees with everyone else from the Super8s onwards combining for 74% (0–95 from

128). Dublin would appear to be maintaining their free kick superiority.

It is not as clear cut as all that however. With the Super8s including long range experts like Michael Murphy, Rory Beggan and Niall Morgan it could be argued that Dublin should be hitting a higher Conversion Rate as they are collectively attempting easier frees.

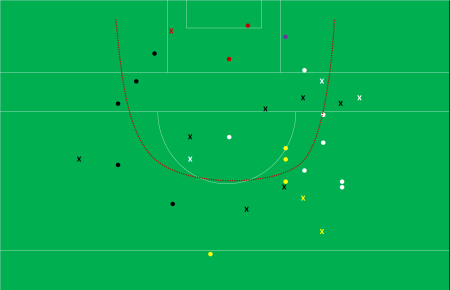

Dublin have taken 55% of their 2018 frees from central locations (an imaginary line up from the D out to the 45 in the above chart) with only four being attempted from outside what I consider to be the optimal range. By contrast only 36% of the other teams’ frees were from this central alley with a not insubstantial 7% of all frees coming from outside the 45. So Dublin’s frees have been appreciably easier.

This is where the Expected Points model comes into its own. On the 22 frees Dublin attempted they were expected to score 18.42 points. They scored 0–18 thus were below average (Expt Pts of -0.42) for these attempts. The other teams had an Expt Pts of 91.26 on the 128 they attempted so the 0–95 scored was 3.74pts above average (Expt Pts of +3.74). Dublin have aided their 2018 Conversion Rate with easier frees but they have not been better free takers per se.

Tyrone however cannot rely on this. Dean Rock has stood up on the big stage before recording a whopping 83% (0-25 from 30; Expt Pts of +3.15) in All Ireland finals and semi-finals in 2016 and 2017. The balance of probabilities is he will deliver again in this final.

There is nothing Tyrone can do to affect Rock’s Conversion Rates (I have no doubt they will try all sorts of verbals, and running across his eye line, but if Lee Keegan’s flying GPS unit in injury time of a final can’t put him off I doubt anything Tyrone do will!). All they can do is cut down the number of opportunities they afford him from frees.

In their most recent non Dublin games Tyrone have given up an average of 6.75 shots at goal from frees (6.5 if we exclude those frees from outside the 45 which Dublin tend to ignore). In their last three games against Dublin they have allowed an average of 4.67 (4, 5 and 5) shots from frees. That is pretty good. This discipline needs to be maintained.

Point attempts

Something similar, in terms of Conversion Rates, is identifiable when it comes to point attempts. Dublin in 2015 – 2017 converted 54% of all their point attempts whilst everyone else was at 46%. In the last four games Dublin have scored on a remarkable 61% of their point attempts (see Table1). Everyone else in that time span has converted 50%. What gives?

Unlike frees – where the main influence on Conversion Rates is from where on the pitch the free was taken from – you can have more constituent parts here affecting the outcome. Location on the pitch is still a deciding factor; as is pressure (see note3) being applied to the defender. Weather can be a factor whilst game state (reviewed here) is also an issue.

Here we are going to focus on two of those – pitch location & pressure applied – but in truth all the above factors can feed in.

Pitch Location

Using our previously constructed central channel as a starting point Dublin again – much like their free taking – help themselves by taking more shots from here. 48% of their point attempts in the last four games come from this region as opposed to 38% for everyone else. But here the similarities end.

Dublin have converted 67% (0–29 from 43) of all point attempts from this central channel and 55% (0–26 from 47) from elsewhere. Everyone else, from the Super8s onwards, is 59% (0-113 from 192) centrally and 45% (0-135 from 303) from elsewhere. Dublin may take easier shots more often but they also convert them at a higher rate.

You may, correctly, say that all these percentages are within any margin of error given the sample sizes. But this phenomenon is not new. In 2017 Dublin were 63% on point attempts from the central channel and 54% elsewhere for an overall Conversion Rate of 58%. Everyone else was 57% centrally, 42% elsewhere and 47.5% overall.

The one trend that is very noticeable this year is just how much Dublin have focussed on shooting centrally. As noted above, and which is very noticeable from the shot chart, 48% of their point attempts have come from the central channel this year – that was consistently in the low 30s the last three years (32% in 2015, 34% in 2016 and 31% in 2017).

Pressure

Looking at the pressure applied to the point attempts we can see that strong or severe pressure was applied to 41% of Dublin’s point attempts and 49% of everyone else’s. It is hard to know if that gap is purely based off Dublin’s fluid movement and decision making or something else. One factor that could aid the gap is game state.

Dublin tend to be involved in more lopsided games than anyone else. Intensity, and as a consequence pressure on shots, drops off in such games. We are getting into very small volumes here but if we only look at point attempts in the first half, when that intensity drop should not be in evidence, do we get the same results? It does narrow the gap; Dublin face strong or severe pressure on 48% of their first half point attempts as opposed to 51% for everyone else.

Dublin’s high Conversion Rates are aided by centrally located shooting and a drop off in pressure in low key second halves. But that shouldn’t belie the skill in evidence – they still convert those centrally located shots at a higher rate than anyone else and manage to take more shots, under less pressure, despite shooting more often from the same crowded central zones.

What about Tyrone’s defence? Is there anything in their recent history that suggest they can affect this? In the seven games under review (see note4) Tyrone have allowed a 50% Conversion Rate on point attempts. About average. This overview masks a pretty big differential however.

Dublin have converted 56% of their point attempts in their three games against Tyrone whilst Monaghan, Donegal and Roscommon combined have converted 45% in their four games.

That 45% is very good. The 56%, when compared to 2017 and 2018 Dublin averages of 58% and 61%, is quite good. Tyrone will need more than quite good here however.

In fairness Tyrone have progressed game on game allowing Conversion Rates of 62% (0-13 from 21) in the 2017 AI SF, 57% (0-08 from 14) in the league encounter and 50% (0–10 from 20) in the Super8 contest. They can allow a high conversion rate off a low base – the league encounter, or a low Conversion Rate off a high base – the Super8 contest. Just not a high Conversion Rate off a high base which is what happened in last year’s semi-final.

Goals

Dublin are known for going for goals. The last four games, excluding penalties, has seen them return 8–02 from 17 shots at goal for a 47% Conversion Rate and 1.53 points per attempt (ppa). Everyone else from the Super8s onwards returned a 40% Conversion Rate (22-09 from 55) and 1.36 ppa.

In 2015 – 2017 Dublin converted 44% of their goal attempts for 1.43ppa whilst everyone else was 38% and 1.23ppa. Dublin are better at taking their goal chances and have been consistently so over the last few years. Quelle surprise!!

Dublin’s higher Conversion Rate is not the real story however. What is really devastating is that they maintain these above average returns whilst going for goal more often. In their last four games they have gone for goal once every 11.4 possessions whilst everyone else has gone for goal once every 18.6 possessions. From 2015 to 2017 they went for goal once every 14.9 possessions versus once every 19.0 possession for everyone else.

There is also the belief that Dublin go for goal early. This was definitely a “thing” in 2017 where the time of their first goal attempt in each game was 09:33 v Kildare (which they scored and then proceeded to goal again on their very next possession), 00:49 v Westmeath, 08:40 against Monaghan and then O’Callaghan’s two salvos against Tyrone @ 04:33 and Mayo @ 01:22 respectively. Five games all with a goal attempt within ten minutes and three with a goal attempt within five minutes.

This has not been as evident in 2018. It was 14 minutes before their first goal attempt against Donegal, their one and only attempt up in Omagh was in the 39th minute and 26 minutes had elapsed against Galway before they had a shot at goal. Only the non-entity of a game against Roscommon produced an early attempt (Costello had his saved on Dublin’s very first possession).

In the seven games in focus Tyrone have allowed 17 shots at goal, or 2.43 per game. In and of itself this is fine however again there is a Dublin/non-Dublin split. In the three Dublin fixtures they have allowed nine goal attempts. That’s three a game, or one every 15.4 possessions, to Dublin and two a game, or one every 23 possessions, to other opponents.

Again there has been an improvement. In their two 2018 meetings with Dublin they have allowed four shots at goal; two a game and one every 23 possessions. You feel that Tyrone will need to replicate this to have any hope but the nagging fear is that, as stated previously, both of those 2018 games were in Omagh. In their Croke Park meeting last year they allowed five shots at goal – can they replicate the Omagh form in Croke Park?

When Tyrone have the ball

Somehow, whilst everyone has been focussing on the blue marvels in the capital, Tyrone have amassed a very nice 60% Conversion Rate in their last four games (see Table2 in the Appendix). Whilst, like Dublin, they were greatly aided by Roscommon (Tyrone converted 79% for their 4–24 whilst Dublin hit 74% in their 4-23) the fear is that, unlike Dublin, the non-Roscommon return of 52% is a more accurate reflection of Tyrone’s level. To this point their 2015 to 2017 shooting saw them return a combined Conversion Rate of 52% with no individual year standing out as particularly accurate (50% in 2015, 49% in 2016 and 56% in 2017).

If Tyrone are not able to do any more than stem the Dublin tide can they show a hitherto fore unseen level of accuracy? In a one off game of course they can but their recent collective history is not so bullish.

Frees

One of Tyrone’s big downfalls in recent years has been their free taking. 2015 to 2017 combined saw them return 65% (2015 = 53%, 2016 = 55%, 2017 = 80%). This is against the backdrop of Rock hitting 88% in the same period. The 2017 mark of 80% looks like they may have hit on a solution however that elevated return was due entirely to Séan Cavanagh who is no longer there. He scored 0–12 from the 13 frees he took last year leaving everyone else to convert 67% (0–08 from 12).

2018 hasn’t seen much progression either. Combined Tyrone returned a below average 71% (Expt pts -0.68) in the last four games and have converted just 69% (0-09 from 13) in their three games against Dublin.

Tyrone know it is an issue (hence why they have had five different free takers in the three games against Dublin). Dublin know it is an issue. The crowd know it is an issue. As such the pressure will get ratcheted up with every miss (think of the pressure on McCaliskey in Ballybofey as he attempted one just before half time after Tyrone had missed three of their first four). At the very least Tyrone could really do with a clean first half here.

In the last three non-Tyrone games games Dublin have been very disciplined allowing the opposition an average of just 3.7 shots from a free with 1.67 in the first half of those games. They have allowed Tyrone just two frees in the first half of each of their three encounters.

Despite this being a weakness for Tyrone it might not manifest itself if Dublin maintain their normal discipline.

Point attempts

Although Tyrone have amassed a total Conversion Rate of 60% in the last four games that has been aided by a 90% Conversion Rate on goals (8 – 01 from 10 shots). This in turn then deflates the Conversion Rate for point attempts to 53% (0–48 from 90). Remove the Roscommon game and it drops to 46% (0 – 31 from 67). In the three games against Dublin it drops further to 41% (0-26 from 63).

There is just no sugar coating this. Tyrone’s point attempts from play have been poor. Very poor.

Part of the problem is shot location. If you recall Dublin are taking 48% of their shots from the central alley whilst the remainder are at 38%. Tyrone, in their three games against Dublin as outlined in the below chart, have only taken 24% (15 of 63) of their point attempts from this alley.

This isn’t a Dublin defensive thing either. In their three games, excluding Tyrone, Dublin have allowed 46% of point attempts from this central alley. Even removing the lacklustre Roscommon game it is still 43% for Donegal & Galway combined.

Just to prove it is more Tyrone than Dublin in their last four games, since the beginning of the Super8s, the volume of Tyrone shots from that central channel is 30% (27 of 90). An increase but still nowhere near the average let alone anywhere near Dublin’s returns.

Tyrone have been shooting themselves in the foot by ignoring the most productive sectors and shooting from what can only be described as sub optimal locations.

Goals

This may come as a surprise to those watching Tyrone of late but they have been relatively shy on the goal shot front. In the seven games under review they have just the 13 attempts with a sequence of 1, 2, 1, 4, 0, 4 & 1. That duck egg is the Super8 game against Dublin in Omagh whilst they have only managed three attempts in the other two Dublin games (a penalty in last year’s semi-final and two in the league game).

All that adds up to 1.86 attempts at goal per game over seven games or 1 every 23.5 possessions. Even more starkly it is 1 per game and 1 every 45 possessions versus Dublin! They will have to do something to create more goal chances.

There is a chink of light however in that Dublin have allowed teams to get in behind them of late with Donegal having three shots at goal, Galway four and Roscommon five. All Roscommon’s five came in the second half when even the pigeons had had enough of the game but still Donegal and Galway combining for seven attempts shows that it is no forlorn hope to step up on their current record

Kickouts

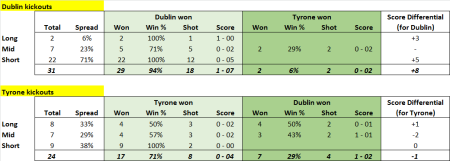

The below table shows the result of kickouts from the three Dublin v Tyrone games. There’s bit to unpick!

First of all, at a macro level, both teams have used a similar enough kickout profile with approx. 50% going short (inside the 45), 33% mid (between the 45 & 65) and 17% going long (past the 65).

On the short ones the returns are broadly (we’re dealing in broad brush strokes here!) in line. Tyrone have lost just the one – which was a throw up after an infringement – but managed to get a shot from 64% of the remainder.

We have seen that Dublin’s Conversion Rates are quite a bit ahead of Tyrone so it is no surprise to see that they have scored 0 – 03 more from the short ones they won. It is a surprise however to see that they converted the ones they won to a shot at a much lower rate than Tyrone (47% v 64%).

That equates to Dublin scoring 0.28pts per short kickout won. Against Monaghan, Roscommon & Donegal combined (see Table3 in the Appendix) Dublin have manufactured a shot from 53% of their short kickouts and scored 0.47pts per short kickout won.

Against Dublin the short ones, both defending against and attacking from, have not really been Tyrone’s problem.

The longer ones are a different issue. At a primary possession level there is no great problem. There have been 62 kickouts that have landed past the 45 with Dublin winning the contest 34–28. At the start of any game you would probably take a 55-45% split against Dublin on kickouts that land past the 45. One step further and Tyrone match Dublin when converting those key primary possessions to shots; Dublin convert them to a shot 59% of the time (20 shots from 34 possessions) with Tyrone at 57% (16 from 28).

It is the scores that come from these longer kickouts that become the problem. Dublin have scored 2 – 13 to Tyrone’s 1 – 07 from kickouts won past the 45. That’s 0.56 points per kickout versus 0.36. This is not unique to Tyrone; against the three aforementioned teams Dublin have scored 0.61 points per kickout won past the 45 and allowed 0.30.

Initially I had thought it was something that Dublin were cleverly doing around Marks but that is not the case. Tyrone have “out-Marked” Dublin 10–6 in their three encounters and scored 0–04 to Dublin’s 0–03 from those Marks. Instead the issue is within those kickouts that land gently into a Dublin player’s stride, past the 45, with no pressure applied.

To break these kickouts down

• Dublin have won 34 kickouts past the 45.

• They have claimed 6 Marks scoring 0–03. That leaves 28.

• Of these 12 were claimed off Tyrone kickouts with Dublin only managing to score 0-01; Dublin may be able to win the Tyrone kickout but haven’t scored off it.

• That leaves 16 of their own kickouts won past the 45 where the ball has hit the deck … but Dublin have scored 1 – 09!

We are in the realm of extremely small sample sizes here and these numbers are not something Tyrone can base a game plan around. But they are unique to Tyrone. Against the other three teams Dublin have won 44 kickouts past the 45 scoring 2-21; 2-06 scored off 16 Marks, 0–10 scored off the opposition’s kickouts (x16) and only 0-05 off their own (x12).

Wrap Up

Dublin are the offensive juggernaut that Tyrone will have to stifle. To do this they will need to ensure they manufacture as many possessions as Dublin, especially in the first half, and maintain their recent discipline in the tackle by offering up no more than five scoreable frees to Rock. They will also have to avoid the dagger of an early goal though luckily for them Dublin may be compliant in this by not going for goal as early as they did in 2017.

After that (sure the first bit is easy!!!) every shot needs to be affected through pressure or location. They need to stay in the game.

Offensively Tyrone have to pick up. They cannot hope to win this game with 70% on frees and mid 40% on point attempts. Although they have not created many goal chances against Dublin we know from the Donegal and Roscommon games that they can. And more importantly that they have been clinical in taking them. If they cannot stem the Dublin attack then they will have to score whatever goal chances come their way.

note1; 95% of all possessions emanated from kickouts (48%) or turnovers (46%) in 2015 – 2017 (9,018 possessions). The remainder came from shots regained (thus the start of a new possession) or throw ins.

note2; As an aside Dublin scored 1-15 from turnovers garnered inside their own 45 (0.38pts per turnover) with Tyrone scoring 0-17 (0.29pts per turnover). Again a function of Dublin’s ability to convert rather than anything Tyrone are (not) doing in transition.

note3; One man’s pressure is another’s loose arm – there is no agreed methodology for tracking pressure but I subjectively give a points range of 0 (no pressure) up to 3 (severe pressure) on each shot to indicate how much the defence pressure shots taken. It is subjective but over time any errors or biases should be applied to all teams evenly so if it is wrong it should be wrong in a very fair and even manner.

note4; The seven games are the three against Dublin, the two non-Dublin super8 fixtures (v Donegal & Roscommon) and their two encounters with Monaghan this year (in Omagh & Croke Park)

APPENDIX

Table1; Dublin shooting by player (Super 8 & AI SF)

Table2; Dublin shooting by player (Super 8 & AI SF)

Table3; Dublin kickouts v Donegal, Roscommon (Super8) & Galway (AI SF)