This piece started out as a simple question – who is the best free taker? Just like reviewing the impact of short kickouts however that simple question opens up differing layers of complexities. So before we can answer that original simple question we need to disentangle the complexity, by understanding the various components, and then put it all back together again. (see note1)

Historic returns

Frees (for this piece 45s are considered free kicks) have produced a relatively stable return for the past number for years though there was a step up in 2017 that has been maintained.

The numbers involved, at just under 2.5k attempts, are robust. We can be happy that the returns, whilst covering approximately one third of all Championship games, are indeed indicative of free taking in the game at the highest level.

2017 – 2019

The relative stability of the returns means that the Expt Pts methodology works well. Thus we are able to look past pure Conversion Rates and take into account the relative difficulty of various frees to see who is outperforming the average

The above table shows the returns for any player with >25 attempts recorded in Championship games from 2017. Why we chose 2017 will become apparent. We can immediately see the importance of overlaying something (in this instance Expt Pts) onto the Conversion Rate through the lens of Rory Beggan. His Conversion Rate is low as the vast majority of his attempts are from distance. But his strike rate on these more difficult attempts is such that it ensures his returns, through Expt Pts, are well above average.

But this table is incomplete. It only includes those games fully charted and in the database.

To ensure a complete picture all frees from games not in the database, for those nine players, as well as the data for another six free takers from Roscommon & Tyrone (see note2), was reviewed and backfilled

Some quick highlights

• Diarmuid Murtagh comes in with a bullet; first on Conversion Rate and an above average return

• A “big three” emerges with Dean Rock, Seán O’Shea and Beggan pulling away from the others in terms of Expt Pts

• Through this lens Conor McManus & Michael Murphy are surprisingly low on the table

• Tyrone’s issues from deadballs are evident. They have used Seán Cavanagh & Darren McCurry as well but their main strikers have been below average as a trio

Shot Charts

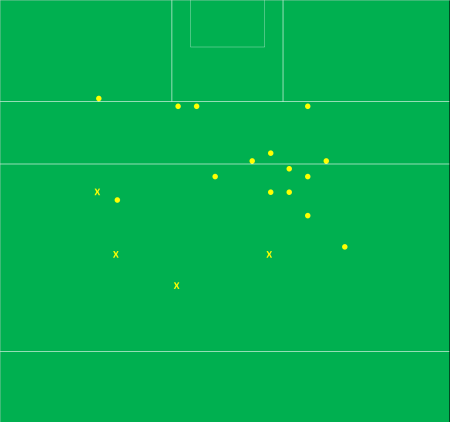

From 2017 onwards I started to chart exactly where point attempts were taken from as opposed to just the sector which feeds into the Expt Pts calculation. This allows us to produce individual shot maps. It has also allowed us to create zones for frees – demarcated by the blue line above- with the guideline returns being 90% for “inside” and 50% for “outside”

In this guise below is Beggan’s shot map since 2017 (yes that is the 65m coming into view!)

He immediately presents a problem (one that we only really see elsewhere with Paul Broderick from Carlow) in that his “outside” shooting is very outside. Given that all attempts from beyond the 45 are placed into three zones based on the width of the pitch no consideration is really given to angle or length. And we can’t really model the returns as there are so few to compare against. It is therefore possible (probable?) that Expt Pts is underselling his performance.

To overcome this I’ve layered another zone so that instead of just “inside” and “outside” we now have “inside”, ”outside” and “ultra” (open to better names!!!). The “inside”/”outside” demarcation was subjectively arrived at after reviewing games. The below “ultra” outline is similarly subjective in nature. It could be moved 1 metre either way. Two metres perhaps? But looking at Beggan & Broderick’s shot maps we do have to introduce the concept so the below is as good an educated guess as any as to where to apply the line.

Individual players

Using these three ranges we now have new averages – 90% for inside, 58% for outside and 34% for ultra. Using these new ranges gives us a very different view of some players

Dean Rock

Mister consistency. Rock is second on the Conversion Rate ranking and first on Expt Pts. He is not padding his stats with short range efforts either. 71% of his attempts are “inside” and, whilst above average, his returns at 93% from this zone are not earth shattering. There are plenty with similar returns. What he is very good at is knowing his range – only two from “ultra”, which were out wide rather than long, with a lot of the “outside” attempts being centrally around the 45. This all aids his excellent 78% from “outside”.

On top of the mere accuracy we must note that 38% of his attempts have come in All Ireland finals and semi-finals. Preliminary work (here) has shown that game state can have an impact on a free taker’s returns. Given the sheer number of big game he has been in it is even more impressive that he has maintained this level of consistency.

Rory Beggan

No. 1 on “outside” shooting, from those with any volume, plus maintaining an above average return on the “ultra” length (40% versus a 32% average without his attempts included). The idea of a wrong side (right footer from the right) dissipates when we are shooting from such long range distances as the narrowness of the angle of the goalposts lessens, however it is still evident in Beggan’s chart. He is deadly centrally (80%; 0-16 rom 20) but if we draw a line up from the edge of the D he is 42% (0-07 from 17) on the right and 55% (0-06 from 11) on the left.

But that is nit picking. His abilities – such length whilst maintaining above average accuracy – is unique and is a deadly weapon. Quite apart from his accuracy just the threat of him means where you foul Monaghan has to come into any opposition team talk – which gives their inside forwards that extra split second to make their runs.

Conor McManus

We can’t talk about Beggan without reviewing Conor McManus. His returns were those that surprised me the most as my go to image of him is always hitting monster points from ridiculous angles. But that image hides a lack of consistency on his free taking; 84% “inside” is poor when you consider the volume he has taken from there.

Now there are mitigating factors. There are five misses from the right (wrong side) which indicates a lack of a reliable left footer whilst the subjective placement of the “inside” line goes against him. A metre further in and five of his misses would transfer from “inside” to “outside”. On top of the five misses inside from the right there are another two “outside”.

There are also another ten misses around the 45 which, when we compare to Beggan’s success there, make no sense as to why he would be taking them. They are obviously outside his zone. But the majority of these were pre Beggan becoming who he is. Eight of those ten central “outside” misses came in the 2017 campaign. Beggan had 12 attempts in total that year. McManus has more or less relinquished those efforts from which he is weakest from.

Seán O’Shea

The GAA’s own holy trinity is completed by Seán O’Shea. His unerring accuracy “inside” gives him a path to overtaking Rock on Conversion Rates but he will want to tidy up the “outside” shooting, especially just to the right of centre, to completely pull away from the other two in Expt Pts

Paul Broderick

Perhaps the most surprising entrant; he is the only member on the list outside of perennial Division1 & 2 teams. That in itself is a testament to the volume of games Carlow have played on their recent journey as well as their willingness to let him have an attempt given his accuracy.

Comments will become repetitive as we go through the players. He knows his limitations so doesn’t take them from the wrong side. The fact that he is left footed helps as “inside” right footed free takers are easier to come by. Again when the angle widens we can see him try some “ultra” attempts from the left. Prone to lapses of concentration – two of his three misses inside are within 25m on his good side.

Diarmuid Murtagh

His accuracy is good but he has been aided by the majority of his attempts being close and central. Again like Broderick the fact he is a left footer helps as Conor Cox & Ciarán Murtagh were able, in the main, to cover his “wrong side”

Neil Flynn

Neil Flynn took over from Kevin Feely as the main free taker in 2018. Overall conversion rate looks low at 71% but as the chart above shows he is reliable with his only two misses “inside” being from (a) the wrong side and (b) a straight on attempt close to the outside range. Has a weakness from centre to right of D for up to ~10metres outside the 45.

Peter Harte

As a unit Tyrone have struggled but Harte has held his own. Again like Diarmuid Murtagh he is aided by the fact that he is, in the main, an “inside” left footed free taker so does not have to take attempts from the wrong side. Again like Murtagh the majority of his attempts are within a specific close in zone – struggles on the edge of the “Inside” zone.

Shane Walsh

The only man to take frees off both feet (white = left foot above, black = right) and it is a testament to his two footedness that he is up there. The only other player I came across with this level of two footedness was Kevin Feely. Walsh was 94% (0-16 from 17) off his left “inside” and 85% (0-17 from 20) off his right. A bit of inconsistency with close in misses whilst Galway could develop a wide/long range shooter to take some of the pressure off as he struggles wide outside

Ciaran Murtagh, Conor Cox & Conor McAliskey

Murtagh & McAliskey had four attempts between them in 2019 whilst Cox’s volume is too small to extract too much from. All three come out with average returns on Expt Pts. Once again a reminder that average here is not bad – this is average in the context of the best players in our game in possibly the era with most collective accuracy ever.

Niall Morgan

Niall Morgan has an obvious comfort zone right of centre around the 45 (81%; 0 – 09 from 11). Everywhere else he has struggles (15%; 0-02 from 13). Playing amateur psychologist Tyrone see these as shots to nothing but there are consequences to such low returns – are they affecting Morgan’s confidence? Could Tyrone have scored more than 0 – 02 if they had gone quick with these attempts? Low volumes but poor enough game management.

Michael Murphy

Michael Murphy’s overall Conversion Rate at 66% is low but the perception, or mine at the very least, is that this was ok given the volume of his long range efforts. To some extent this is true as just under half (36 of 74) of his attempts come from “inside”.

And he is as good as the next man from “inside”. But this perception hides the fact that his long range shooting has not been up to scratch. He is, or at least has shown in Championship, that wide left, when he has, from distance, to swing them in, does not suit him.

For “outside” his returns of 45% are well below the average of 57%. Even more so when compared to those of the holy trinity – Rock, Beggan & O’Shea combined for 71%; 0-55 from 77.

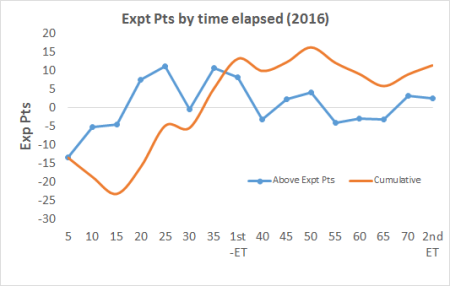

Cillian O’Connor

In many ways Cillian O’Connor is the hardest player to peg. And the most surprising. I wrote on this subject, in what feels like a different lifetime, back in 2016 when O’Connor came out on top. He was the Dean Rock of 2013 – 2016. But this portion of his game has obviously regressed from there.

His “inside” shooting is still as metronomic as ever with his only misses coming from the right (due to the fact that Mayo have been unable to rely on a left footed free taker) and two out wide right on the subjective partition line.

The original “inside”/”outside” demarcation was not built on O’Connor’s data but it could well have been. The minute he steps outside that range his returns begin to plummet, from 94% “inside” to 41% “outside. This is the biggest drop of any player with any volume. The cherry on top being that he has missed all six from the “ultra” range.

Mayo have to help O’Connor here. Develop a left footed free taker. Transfer those longer range attempts to someone else. His brother perhaps? If you can’t do either start going short. Do something because what has happened for the last three years hasn’t worked.

Appendix

Note1: We must also understand that there are elements not captured. The impact of weather. The differing grounds. Pressure. Taking a free one point behind in an All-Ireland final is very different than taking one when ten points up in a Leinster final. We know all of these have an impact but that impact is not measured here.

We must also always be cognoscente of the small volumes involved

Note2; Roscommon & Tyrone were chosen given their relative success in the timeframe. We had the main free takers for the other “big” teams. Both of these had made the Super8s in both years