• Can Glen profit from the big chances they create through their kicking game?

• Will Kilmacud’s shot execution be better? And will Walsh & Mannion be as subdued (from play) as in the 2022 final?

• Bench impact

• Kickouts; will both teams go long against the press? And can either middle third gain an advantage.

Ignoring the 16th man controversy, the closeness of last year’s final, where Conor Ferris produced a truly magnificent reactionary save to deny Conor Glass in the second minute of injury time, will have had both teams poring over the video during the Christmas break looking for that slight edge. Is there anything we can see in that game that will guide us to what both teams will focus on?

Styles of play

Glen

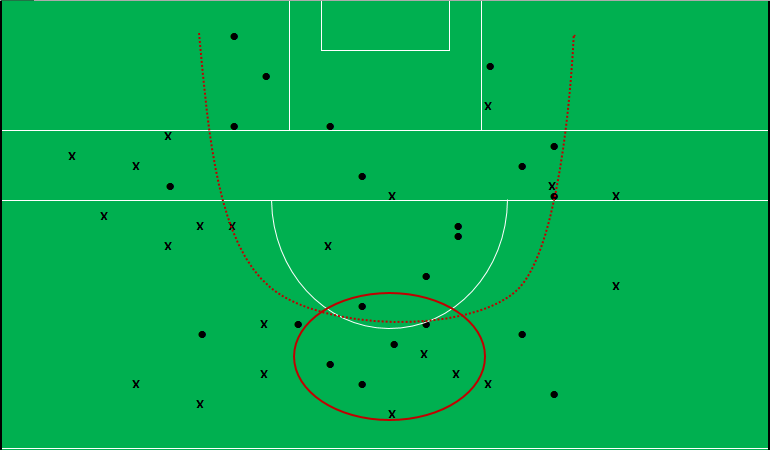

The final in 2022 was the classic clash of styles. Glen, the counter puncher, bookending Danny Tallon’s goal off their first possession with the save from Conor Ferris in the 62nd minute. They had two other clear-cut attempts at goal in between – Stevie O’Hara tripping on his left whilst through one on one and Conleth McGuckian with that infamous scramble against the sixteen men.

Glen were much more willing to use the attacking kick – letting the ball go into one-on-one contests much more frequently. 69% (22 of 32) of their possessions included what was marked as an attacking kick pass.

Those twenty-two possessions led to ten shots, four of which were the goal attempts. When they produced the attacking kick it was all in. Nine of those possessions only had one or two players control the ball. Twenty of the twenty-two had less than ten players control the ball.

Glen got the ball, looked up, tried to deliver a kick pass and when delivered committed to the fast strike.

This ethos has survived through 2023. Combining their Ulster final and semi-finals, against Scotstown and Naomh Conaill respectively, 55 % (39 of 70) of their possessions contained an attacking kick pass. This may be down on the 2022 final however that reduction, and the fact that they have not really threatened the goal in those two games (one attempt across the two games), can be attributed to both the weather and the defensive set ups they faced. The opposition combined for just a 42% attacking kick rate (31 of their 74 possessions contained an attacking kick pass) in those same games. Glen are still looking to strike faster than their opponents.

This style of play is fast, exciting and should produce excellent opportunities for their attackers to have a go in one-on-one situations. Against Moycullen in the 2022 AI semi final they produced two goal opportunities – one direct from a throw when the teams are lined up man on man.

What this high variance style can lead to are long spells without the ball and without a score. It is the ultimate balancing act for fast transitional attack teams. If you have four possessions, where you lose three one-on-ones due to variance and do not manage a shot from the one you do win, you can go ten minutes without scoring and can invite pressure if the opposition produces shots and then pushes up on your kickout winning one or two of those.

In last year’s final Glen did not have a shot in the first half from the 14th minute. Never mind a score – they did not have a shot. Similarly, after Stevie O’Hara’s missed goal attempt in the 48th minute the only shots they produced thereafter were the two goal attempts in injury time. It is to their absolute credit that they had the mental strength to overcome those barren patches, but you feel it is something they will have to address on Sunday.

(Against Naomh Conaill they used their kick passing differently claiming five Marks as the defence dropped. Unfortunately, they missed the last four. And missed the one they attempted in the final against Scotstown. Not sure we will see them revert to this ploy against Kilmacud!)

Kilmacud

If Glen are the counter puncher, then Kilmacud assume the orthodox stance controlling the centre of the ring and continually scoring with percentage attempts.

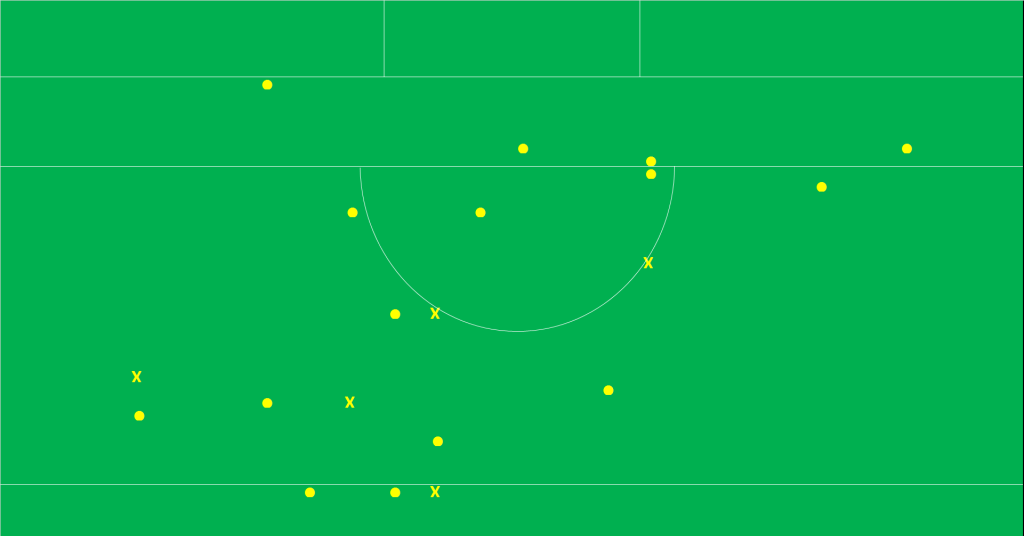

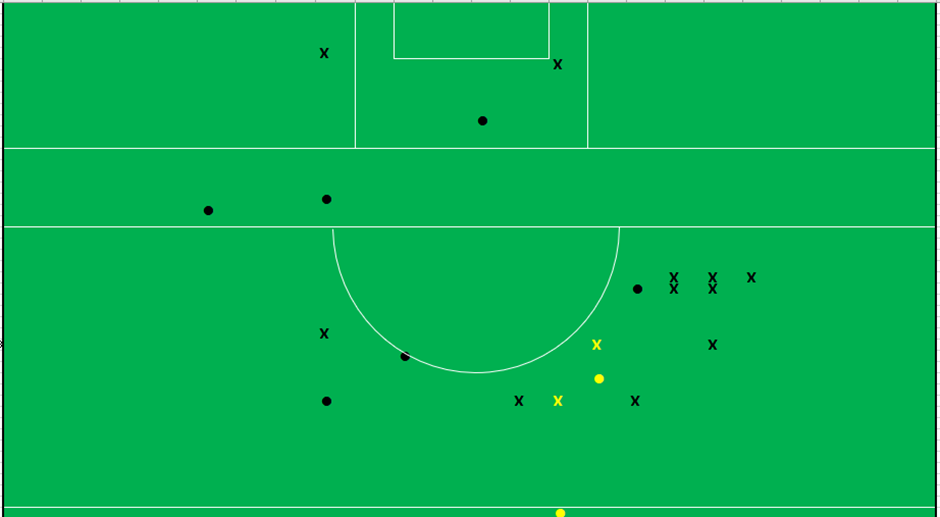

47 minutes into last year’s final Glen were leading 1-09 to 1-07 but the shot count was 21-14 in Kilmacud’s favour. The shot chart, below, to that point was fine and tidy; nothing wild. It was the execution that let Kilmacud down including two missed attempts from Paul Mannion and a missed free apiece for Mannion and Shane Walsh. Kilmacud should really have been at least level at that stage.

(As a side note Glen restricted Walsh to just one point attempt from play and two primary assists. He was good on deadballs scoring 1-03 from five attempts keeping the scoreboard ticking over but noticeably quiet otherwise. Mannion was also quiet scoring 0-01 from three frees and missing his only attempt from play. Outside the final free from the sideline, he was primary assist on only one other shot)

The game ended with Kilmacud producing 27 shots to Glen’s 14. Again, until the goal scramble in injury time this was 27 – 12.

How they produced double the volume of shots was through controlling the ball. They had 35 team possessions to Glen’s 32 but had 99 possessions inside Glen’s 45 (Glen = 59) and 14 inside the 21 (Glen = 11). They continually recycle until the correct opportunity presents itself.

That is what made the Conversion Rate of 44% in the final so noteworthy. Kilmacud are a control team. Process driven. Correct shots at the correct time with the correct outcome. The final component malfunctioned last year.

Glen cannot rely on that malfunction this Sunday, however. Against Naas in the Leinster Final Kilmacud’s shooting was back on point. Again, the control was there; 97 player possessions inside Naas’ 45 from 35 team possessions. Twenty shots this time but the Conversion rate was 75%

One other noteworthy point from watching the game back was the impact of Kilmacud’s bench. They introduced Cian O’Connor in the 46th minute and Shane Horan in the 50th. Combined they were involved in all of Kilmacud’s final six shots – taking two scoring 0-01, winning two frees that were converted by Walsh, winning a Glen kickout that led to another free and being involved in the build up to Mullin’s point in the 48th minute.

For Glen they had O’Hara’s one on one but nothing outside of that.

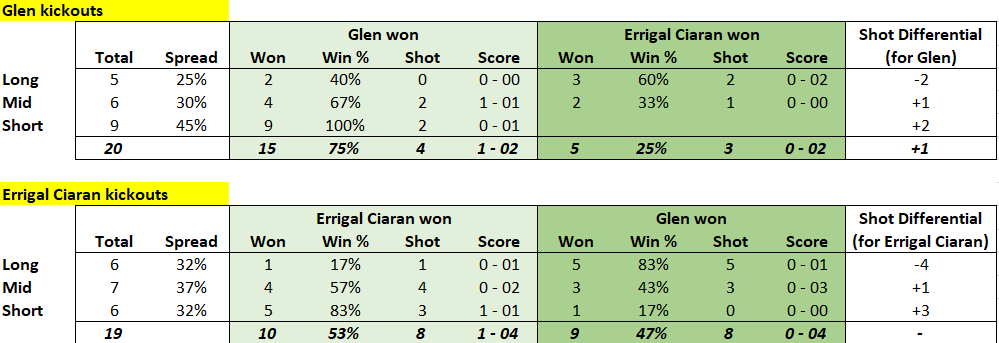

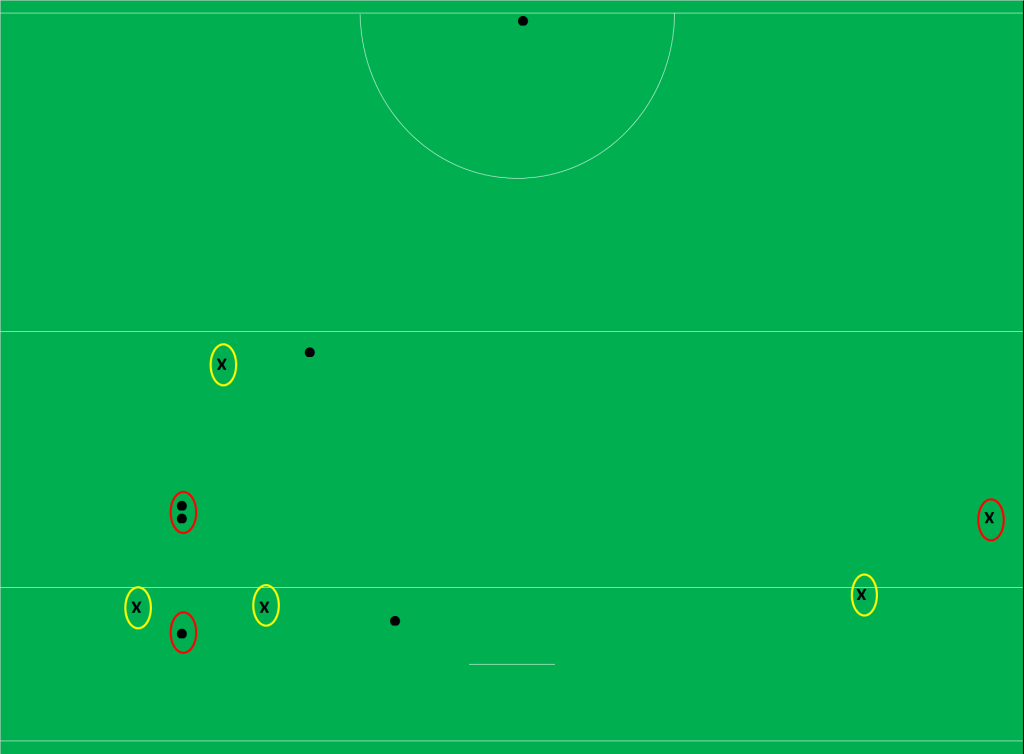

Kickouts

The Battle of the presses. Thirty kickouts in last year’s final with eight going short, four just over the 45 and the remaining eighteen going long. Of the eighteen that went long possession broke down evenly – nine apiece. You might think that the kickout team would control those longer kickouts as they know where the ball is going etc. however both teams were better at claiming the opposition’s kickout on those longer ones. Twelve of the eighteen long kickouts were lost by the kickout team.

Part of this may be the length of both keeper’s kickout, as neither were able to get beyond the opposition 65 but is more probably a reflection of both team’s midfield. The Kilmacud keeper has changed this year, with David Higgins replacing Conor Ferris, but against Naas there was no evidence of any extra length. That is heavily caveated however as very few of the kickouts against Naas went past the 45.

This is one of those hidden advantages to Kilmacud’s positive shot count. More shots = more opposition kickouts. You get to decide if you press of drop. If you press you can compress the landing zone due to the lack of length. Kilmacud get to do what they love best. Control the tempo.